Rising Energy Prices Will Hit Poorest Households Hardest

By Reuters energy reporter and columnist John Kemp

Rising energy prices come at an awkward time for governments and central banks trying to support the recovery and wanting to run a high-pressure economy to boost jobs and wages for lower-income groups. Policymakers will try to “look-through” the acceleration in inflation caused by rapidly rising energy and food prices, arguing policy should not respond to idiosyncratic rises likely to be “temporary” and quickly reversed.

But households and businesses have no such option: their spending will be directly hit by the increase in fuel and food costs unless they can secure offsetting increases in wages and revenues.

In the United States, energy prices increased at a compound annual rate of almost 7% per year over the two years to August...

... while food prices had risen almost 4% per year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Rising energy and food prices will hit lower income households hardest because they spend a much higher proportion of their income on these items (“Consumer expenditure survey”, BLS, September 2021).

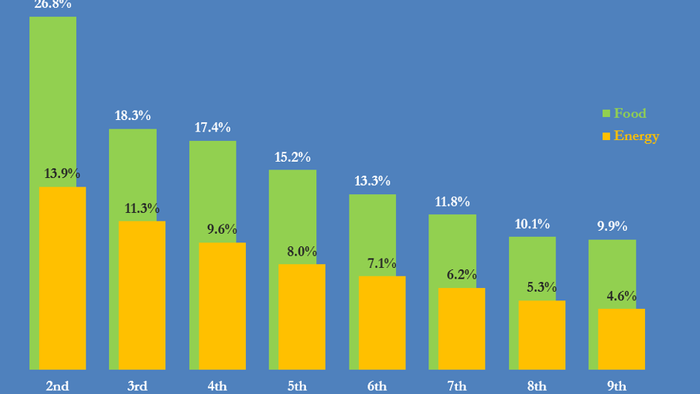

In 2019, before the pandemic, U.S. households in the second-lowest income decile spent 27% of their post-tax income on food and 14% on energy, compared with 10% and 5% respectively for households in the second-highest decile (https://tmsnrt.rs/398MSml).

The same problem will hit lower-income households across Europe and Asia because they also spend a much higher share of their incomes on food and fuel, ensuring the price increases have a regressive impact.

Not everyone experiences price rises in the same way. Households in lower-income deciles are currently experiencing much faster inflation rates than those in higher deciles because of their different spending patterns.

Squeezed Hard

Rapidly escalating food and fuel prices have microeconomic, macroeconomic and political implications which make them impossible for policymakers to ignore.

At a microeconomic level, they will intensify financial pressure on poorer and lower middle-income households, which are least able to absorb the cost increases and experience deteriorating living standards.

In England, there were already 3.2 million households (13.4% of all households) struggling with fuel poverty, as defined by the government, before the pandemic (“Fuel poverty statistics in England”, BEIS, March 2021).

At the macroeconomic level, lower income households will be forced to reduce spending on other items, which will act as a drag on other economic activity, creating headwinds for growth and employment.

Politically, the concentrated impact on lower-income households, which contain lots of swing voters, will ensure rising food and fuel prices are impossible for politicians to ignore.

In the United States, the Biden administration has opposed tax increases that would raise the cost of gasoline and accelerating inflation has become a sensitive congressional issue.

In Europe, governments in Spain, Greece and Italy have begun to respond to the upward pressure on gas and electricity prices by considering rebates and tax changes designed to keep overall bills down.

Political attempts to limit food and energy price rises are often derided as “interference” with price signals, but they are rational for policymakers who must worry about being re-elected.

Squeezed Hard

Rising food and especially energy prices also push up the cost of other goods and services because they are among the most widespread input costs for nearly all manufacturers, distributors, retailers and service providers.

In the United States, consumer prices for items other than food and energy increased at a compound annual rate of more than 2.8% in the two years to August, the fastest for almost a quarter of a century.

In the short term, non-food and non-fuel inflation may have peaked as the re-opening of the economy was largely completed by early summer, and a resurgence of coronavirus cases has induced more caution about travel. U.S. core consumer prices excluding food and energy increased at an annualized rate of 5% in the three months to August, down from almost 11% in the three months to June, the fastest for nearly 40 years.

But renewed increases in the cost of food and fuels could filter through into another round of broader price increases later this year and into 2022 as households and businesses try to offset the impact.

There is still a lot of inflationary pressure still in the pipeline in terms of raw materials, shipping and logistics costs, which will continue filtering through into consumer prices over the next twelve months.

If households and businesses succeed in pushing for wage and revenue increases to offset rising input costs, faster inflation will become more entrenched, becoming harder for policymakers to ignore. If they don’t succeed in forcing through wage and price increases, inflationary pressures will burn out, but output and employment growth will likely slow as a result as real incomes fall. Tyler Durden Thu, 09/16/2021 - 12:20

http://dlvr.it/S7htZB

No comments:

Post a Comment