Goldman's Clients Are Asking How Various Inflation Regimes Affect Stocks: Here Is The Answer

Picking up on a joke we made earlier this week when we called Joe Biden the Six Trillion Dollar Man (in homage to a very deflationary Lee Majors) in response to the 12 zeroes contained in his budget, in his latest Weekly Kickstart note Goldman's David Kostin writes that...

by at least one measure, inflation has been rampant during the past 50 years, noting that in 1973, Steve Austin was the most powerful man in the world, with super strength in his right arm, a bionic eye, and artificial legs that could run 60 mph. It cost the federal government $6 million to re-build the NASA astronaut into the bionic man, played by Lee Majors in the hit TV series, “The Six Million Dollar Man.”

Fast forward to today, often sporting his trademark 1970s-style aviator sunglasses, President Joe Biden is the most powerful man in the world.Biden is the $6 trillion man when his three 2021 fiscal spending plans are combined: the $1.9 trillion COVID relief plan that was passed in March, the $2.0 trillion American infrastructure plan proposed in April, and the $1.8 trillion American families plan proposed in May. If all three proposals are passed by Congress, it would represent an unprecedented level of peacetime spending in relation to the size of the underlying economy. Of course, it remains to be seen whether the latter two plans pass Congress.

And while it increasingly looks like Biden's original $6 trillion proposal will be substantially reduced - and may even collapse should it not gather the required support from centrist democrats - Goldman's economists did not wait to find out what happens and recently raised their near-term inflation forecasts even as they maintained their expectation that inflation will begin to abate later in the year. In April, both core PCE (+3.1% y/y) and core CPI (+3.0% y/y) exceeded expectations and notched highs not seen in more than two decades. In turn, Goldman's economists expect that core PCE will register 2.5% at the end of 2021 and decline to 2.1% during 2022.

To be sure, after initially freaking out about a deluge of inflation, the growing likelihood that Biden's stimulus package will be materially diluted is why equity market performance has already shown a recent unwinding of inflation concerns. As Goldman notes, In March, amidst fears about rising inflation, stocks with high pricing power

... began to outperform those with low pricing power, reversing 5 months of low pricing power outperformance as the economy recovered. However, during the past few weeks, low pricing power stocks have outperformed again (7% vs. 3%). At the same time, the interest rate 10-year inflation breakevens has declined by 14 bps to 2.4%, suggesting inflation fears priced by both equity and debt markets are easing.

Not surprisingly, this whiplash has prompted most of Goldman's recent client discussions to focus on inflation and its implications for equities.And, as Kostin explains, investors ask just one thing: “how does inflation affect corporate earnings and stock valuations?”

Answering this recurring question, Goldman's Kostin notes that while inflation has mixed implications for earnings, it is generally a positive (as long as it is not hyperinflation in which case all bets are off of course). Kostin then reveals that in the bank's top-down sector-level earnings models, inflation consistently has positive coefficients for sales and negative coefficients for margins. On net, however, Goldman argues that "the boost to nominal sales growth through rising prices typically more than offsets inflation-driven margin compression." While one can debate this, it is certainly the case that companies with revenues tied to commodities, like Energy, or interest rates, such as Financials, are the largest beneficiaries from strong inflation regimes.

That said, inflation becomes a headwind to valuations if it leads to expectations of Fed tightening and thus higher real interest rates. And as Morgan Stanley has argued as part of its mid-cycle transition thesis, S&P 500 returns have been consistently positively correlated with breakeven inflation but valuations have typically contracted alongside sharp increases in real interest rates (as a reminder, MS expects PE multiples to shrink 15% in the next 6 months).

On the other hand, and adding to the complexity, the Fed has indicated it will not tighten the funds rate before seeing prolonged labor market improvement resulting in broad wage gains, particularly at the lower end of the income spectrum. In the past, the S&P 500 P/E multiple has typically expanded during periods of falling inflation and interest rates.

For the record, Goldman's economists forecast the yield curve will steepen in 2021 and 2022, with the funds rate unchanged while the 10-year yield rises from 1.6% today to 1.9% and 2.1% at year-end 2021 and 2022.

Here Kostin makes another valiant attempt to ease worries about runaway inflation, claiming that although inflation is generally a negative impulse for valuation multiples, "recent popular investor focus on earnings yield less the inflation rate is misplaced" and here's why:

Investors concerned by this metric note that it has fallen to its lowest point since the peak of the Tech Bubble in 2000 and suggests the return from owning equities is erased by inflation. We disagree with this interpretation. First, equity earnings and the prices tied to them are nominal and typically rise with inflation. Second, even inflation hawks agree that the most recent prints are biased by base effects and reopening dynamics. In contrast to the gap between the earnings yield and inflation, the EPS yield gap versus the 10-year US Treasury yield, which is commonly used as a proxy for equity risk premium, actually remains above its long-term average. See Exhibit 1.

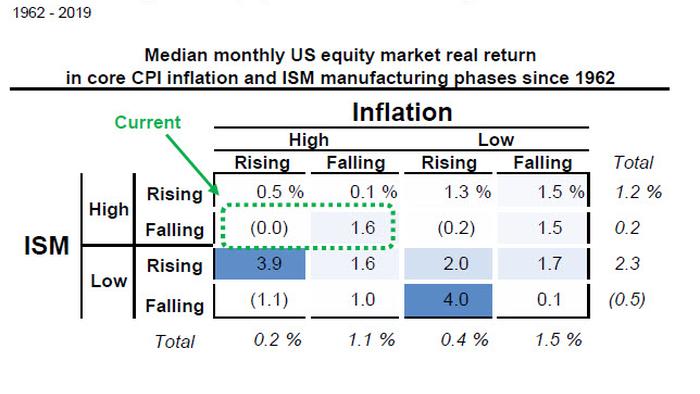

Kostin's spin aside, it is undisputable that overall, stocks perform better during periods of low inflation than when inflation is high. Goldman categorizes periods since 1962 into those of high and low inflation by comparing year/year core CPI to the Fed’s estimate of consensus long-term inflation expectations. Exhibit 2 clearly shows two inflationary regimes during the past 60 years: The first 20 years (1962-1980) and the past 40 years.

During the first period - which culminated with Volcker hiking rates to 20% - core CPI averaged 5.3% and registered above the long-term estimate 69% of the time.

Since 1962, both pre-and post-1980, the median monthly US equity market real return during high inflation environments has been an annualized 9% vs. 15% during periods of low inflation. As shown in the chart below, periods of high inflation have corresponded with the outperformance of Health Care, Energy, Real Estate, and Consumer Staples sectors, while Materials and Technology stocks have fared the worst in high inflation environments. Surprisingly, Value and Size factors have not performed very differently in periods of high versus low inflation.

Finally, drilling down a little deeper, equity performance has differed greatly in periods where inflation was high and rising versus high and falling.The median monthly market real return has been 2% annualized in phases where inflation was high and rising vs. 15% when inflation was high and falling. At the factor level, Value has generally fared better when inflation was high and rising than when it was high and falling. Among sectors, although Energy and Health Care have outperformed in periods of high inflation, they have performed much better when inflation was rising than falling.

Tyler Durden Sun, 06/06/2021 - 19:00

http://dlvr.it/S1C1jm

No comments:

Post a Comment